Do you know your polygenic risk score for heart disease?

- Ali Zaidi

- Oct 1, 2025

- 4 min read

TLDR:

Polygenic risk scores estimate risk by summing thousands of small genetic effects.

For heart disease, high PRS can reveal hidden risk even when traditional risk factors look normal.

Genetics do not change over time and therefore provide a lifetime risk assessment

Genetics are not destiny—lifestyle and medical prevention remain powerful.

Clinical use is emerging but not yet standard; watch for guideline updates as trials mature.

As someone who is proactive about my health, I am always looking for better ways to understand—and reduce—my risk for disease. As the leading cause of death in men and women across the globe, coronary artery disease (CAD) is high on my list of things I want to prevent. Unfortunately, traditional risk factors such as age, high blood pressure, high LDL, diabetes, and smoking do not account for all the cases of CAD. The coronary artery calcium (CAC) score can add additional information about your risk of having a heart attack in the next 10 years. However, a CAC is not useful for someone less than 40 years old (unlikely you will have calcified plaque under 40). What if you could evaluate someone’s risk for CAD beyond traditional risk factors and before they developed calcification in their coronary arteries?

Enter polygenic risk scores (PRS)

As the name implies, polygenic risk scores involve evaluating many gene variations to calculate risk. Researchers analyze DNA from thousands of people to find genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)) associated with a particular disease. Each SNP contributes a small increase or decrease in risk. Weights are assigned based on how strongly each variant is linked to a disease. A person’s PRS is the sum of their genetic variants multiplied by these weights.

PRS testing is available for several conditions, including heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. Over time, incorporating PRS into clinical risk assessment for a variety of diseases may become routine.

We’ve long known that heart disease runs in families, so it makes sense that genetics could help predict risk. How well does PRS stack up against traditional risk factors?

In the UK, researchers followed ~45,000 patients without heart disease to see who developed a major cardiovascular disease event—defined as CVD death, heart attack, acute coronary syndrome, coronary revascularisation, or stroke. Among younger patients (40-54 yrs old), traditional risk factors identified only 26.0% of those who had a major CVD event, while the combination of traditional risk factors and PRS scores identified 38% of cases - nearly 50% more cases (reference). Because age is a dominant factor in standard calculators, younger adults are often underestimated and PRS fills that gap.

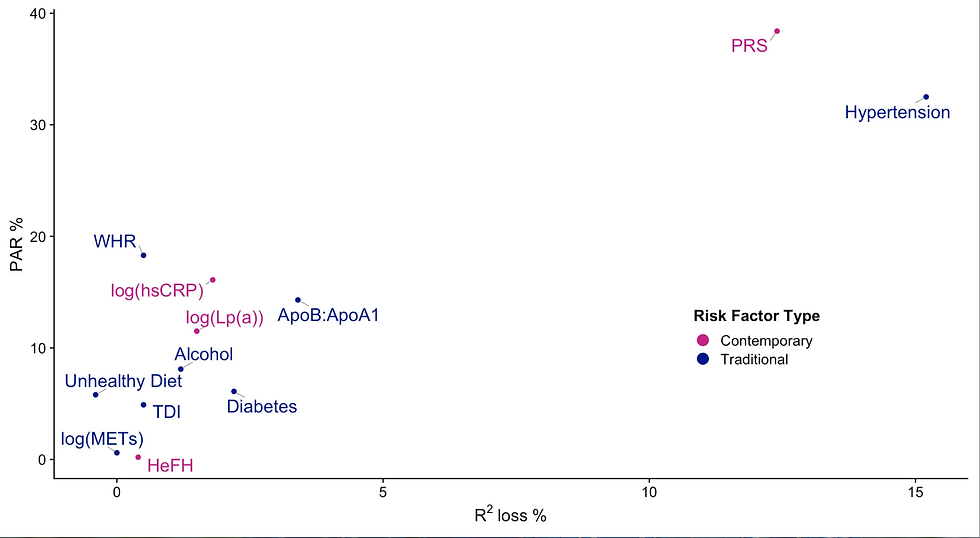

Similarly, researchers at Harvard followed ~300,000 patients for over a decade and monitored who developed a heart attack (reference). The graph below is their assessment of the risk factors associated with heart attacks:

A high PRS score was a stronger risk factor than every risk factor evaluated (diabetes, high cholesterol, Lp(a), unhealthy diet, high waist-to-hip ratio (WHR)) other than high blood pressure.

One criticism of these genetic studies is that the samples typically come from predominantly European samples and may not have as much predictive value in more ethnically diverse populations. To help evaluate this question Rana et al looked at a multi-ethnic group of approximately 60,000 patients at Kaiser Northern California (reference). The highest PRS quintile carried a 66% higher CAD risk (adjusted HR 1.66) compared to the lowest quintile. This suggests PRS retains predictive value across diverse populations

In 2023, the American Heart Association published a scientific statement affirming that PRS scores “have been shown to be strong predictors of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and independently prognostic of CAD risk (1.4- to 1.6-fold per standard deviation of the CAD PRS), including self-reported family history and comparable or more powerful predictors of CAD than individual clinical risk factors”(reference). I found this graph in their publication very interesting.

The panel on the left shows the net reclassification index which quantifies how well a model reclassifies individuals into more appropriate risk categories when PRS is added to clinical risk factors. The benefits for African Americans and European were small, but the benefit for Hispanics and South Asians were moderate - although the confidence intervals were wide suggesting uncertainty in the data. Perhaps for Hispanics and South Asians, genetics plays a more important role in heart disease.

The panel on the right shows the C-statistic (or area under the curve) which measures discrimination—the probability that the model correctly ranks a person who develops CAD higher than someone who does not. We see that PRS alone outperforms all the individual risk factors and when combined with all the risk factors, improves prediction.

The AHA statement concludes: “The inclusion of PRS in the AHA/ACC ASCVD risk calculator significantly improves prediction, and early evidence suggests that targeted screening may be cost-effective.”

Getting tested

A cheek swab or saliva sample is all you need. PRS tests with clinical studies supporting their use include include Allecia and Genincode (used in the Kaiser study cited above). These tests require a doctor’s order and are not typically covered by insurance. There is no gold standard test; each test looks at different SNP’s and calculates their own PRS.

Presumably, if you learn that you have a high PRS for heart disease, you might be more aggressive about lowering your risk factors. A study of 200 patients aged 45-65 yrs old randomized one group to receive a conventional risk factor score vs. the conventional risk factor + PRS. The group that also received a PRS was more likely to start a statin and had lower LDL cholesterol after 6 months of follow-up (reference). Sometimes knowing that you are at high risk is motivational.

Polygenic risk scores aren’t a crystal ball—they don’t guarantee who will or won’t develop heart disease. But they do offer a glimpse into your inherited susceptibility long before traditional markers or plaque appear. For younger adults or those with a family history of CAD, PRS can provide an early warning and a powerful motivator to adopt heart-healthy habits or discuss preventive therapies with your doctor. As research broadens to more diverse populations and testing becomes more accessible, PRS may soon become a standard part of personalized cardiovascular prevention—helping us shift from reacting to heart disease to preventing it altogether (Medicine 3.0!).

Comments